I remember talking to a birthright Quaker, when I was still flirting with the idea of becoming a member. “Birthright” means that she was born into and brought up in the Religious Society of Friends. “As children,” she told me, “we used to play a game on coaches to London. We’d play ‘Spot the Quaker’. We could tell them by the way they looked. Sensible shoes. Sensible clothes. Women with sensible haircuts.” Looking round Friends House, I could see what she meant. This is ironic, because I can think of few groups where explicit rules and conformity play a smaller part. We’re a bloody-minded, idiosyncratic bunch: no one tells us how to dress; it’s just part of our lived testimony of simplicity, I suppose. And while I can do ‘simple’, the dandy in me sometimes has to share the stage.

In four separate posts, I will look at the role of attire in my own schooldays, my time at university, my business career and in my vocation as a teacher.

Finally, and in the fifth of the four posts, I am going to advocate an approach to school attire that suits me as comfortably as the well-worn navy Boden shorts I slouch around in, or my favourite Pakeman, Catto and Carter navy serge suit. It is based on forty years of conscious clothes-watching. And if it’s not right for you, who am I to judge?

Pre-history

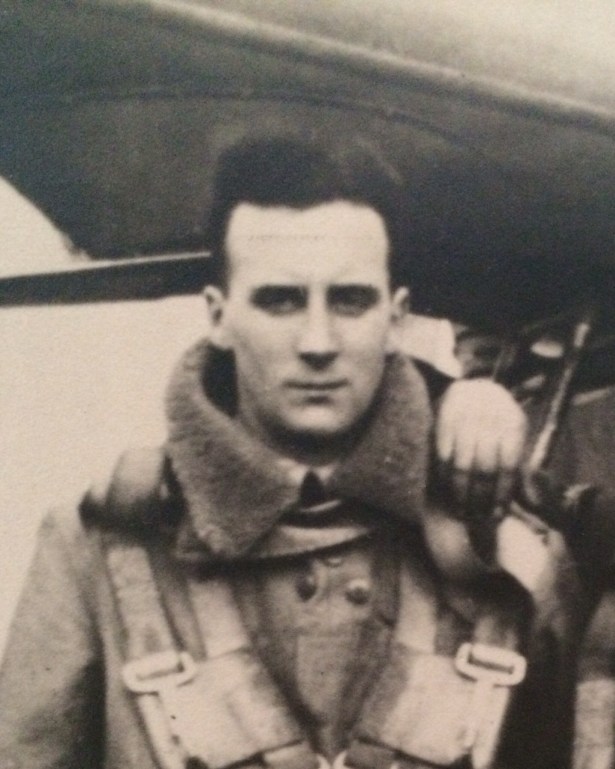

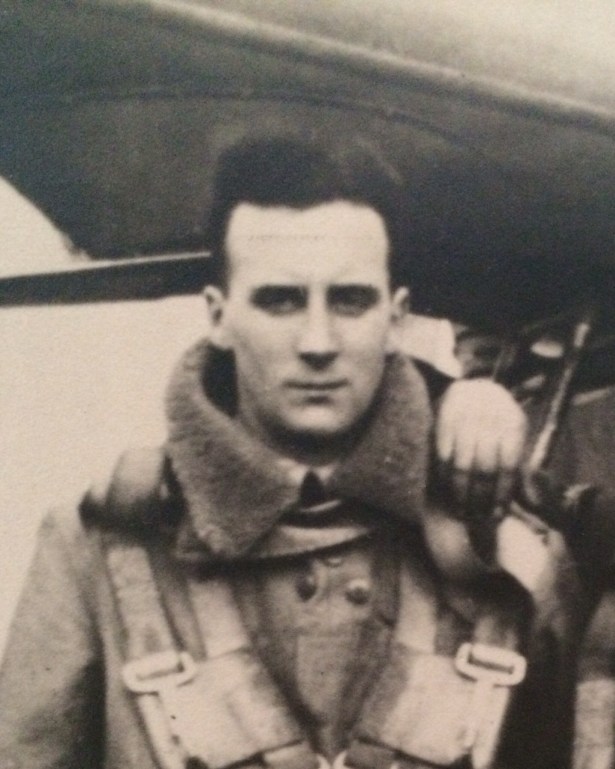

I need to mention my grandfathers. All three of them (you will gather by now that I am creative with my maths) wore a uniform in their career. My identity was marked by their example, in many ways.

Pilot Officer Joseph Unsworth DFM was killed in action in 1941. My grandmother married again, a Flight Sergeant.

My father’s father was a policeman.

My father’s father was a policeman.

Pakistan

My first memory of a teacher’s attire was Mrs Malick, in Lahore.

Mrs Malick, beside our tonga.

Mrs Malick, beside our tonga.

I was in second grade. The English wife of a Pakistani man, teaching at an American school, she wore modest, Pakistani clothing. Judging by the photograph, she looked smart, though I remember her manner and bearing far more than her clothing.

Here are a couple of the 18 year-olds at the school, to show you my first influences. One the cusp of two generations: the conformist and the hippy.

Primary School

There was a brief blur of skirts and sweaters from Mrs Herring and Mrs Snowden at my primary school in Luton. I can only imagine that they reflected the early seventies. And then I was off to my prep school. Up until that point I’d worn my own clothes in Pakistan and the usual kit at Maidenhall (a maroon and pale blue tie comes to mind).

Preparatory School

Bedford School was very different: I was taken up to Selfridges to buy grey jackets and shorts. I’m not sure who was more excited: my parents or me; I just remember going round to a neighbour in our little cul-de-sac at the bottom of Dallow Road, bursting to show off my new uniform. I must have seemed such a stuck-up little prig to my friend Michael, the son of a Vauxhall Motors worker. In fact, our financial circumstances weren’t that different; it was just that the government pays its overseas civil servants, of whatever grade, to send their children to boarding school.

By the way, my daughter was equally proud of her school uniform. Before she’d turned four, she was kitted out in a grey pinafore, brown leather mary-janes, a pale blue polo neck and a straw hat.

Wilful and bossy even at that age, she made me parade her round London in her special new clothes. We are alike in many ways.

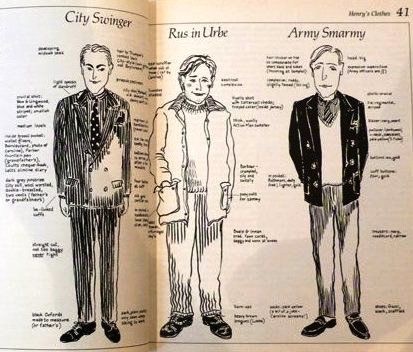

Class and Conformity

Clothing denotes class: be in no doubt. And I turned up in the wrong grey suit. Everyone else’s came from Beagley’s, the school outfitters; mine, though more expensive, was ‘not one of ours’. Nor did my royal blue t-shirt and light cotton shorts match the rugby jerseys and heavy rugby shorts that every other boy wore for football. My clothes subtly marked me as an outsider when all I really wanted to be was deep inside the camp.

My teachers, male now, wore tweed jackets and grey trousers or somber suits, sometimes in three pieces. And they wore gowns; sometimes hoods (for special occasions). Some of these men had History: my form master had been a rubber planter in Burma, then led his troops against the Japanese there. My house master had spent the war in Changi and died in the summer term of my second year at the school. My Latin master had fought in the desert campaign and had lost the use of his right arm (his handwriting, though legible, was marked by the war). Their tweeds, gowns and suits particularly stand out in my memory. As for the rest, PE teachers wore smart track suits, most science teachers wore white jackets and the D&T teacher had a blue coat for the workshop. We all had our uniforms, which showed where we fitted in.

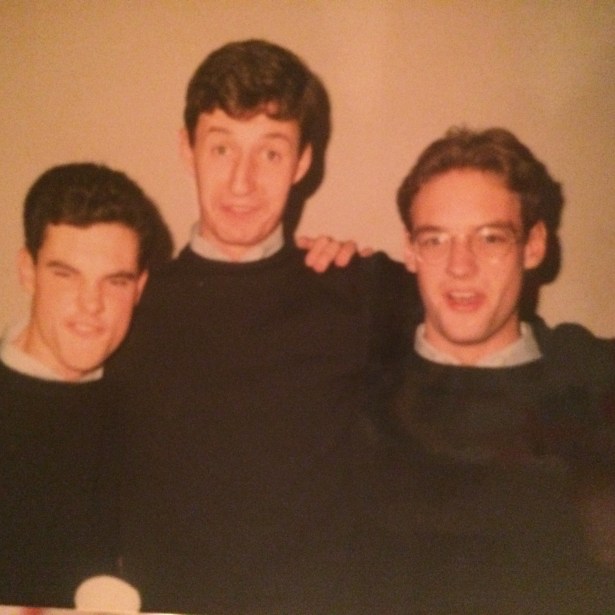

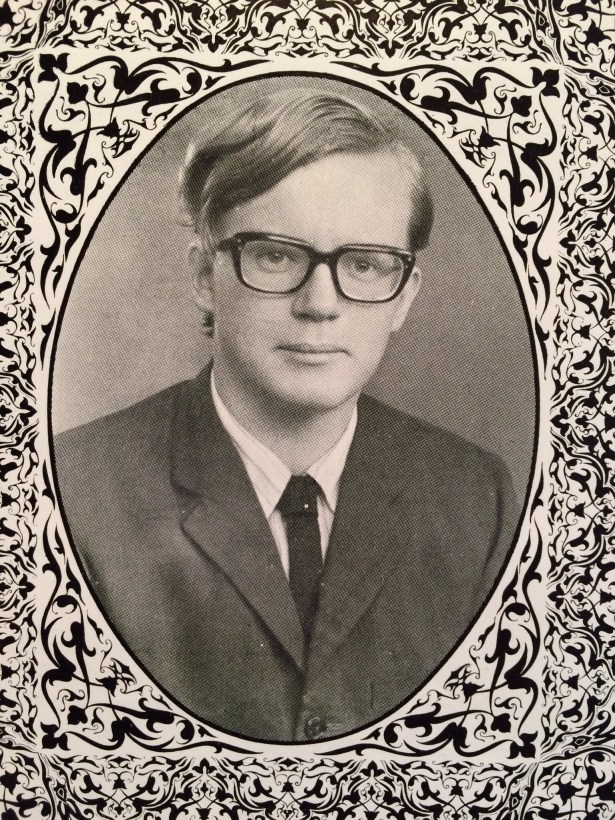

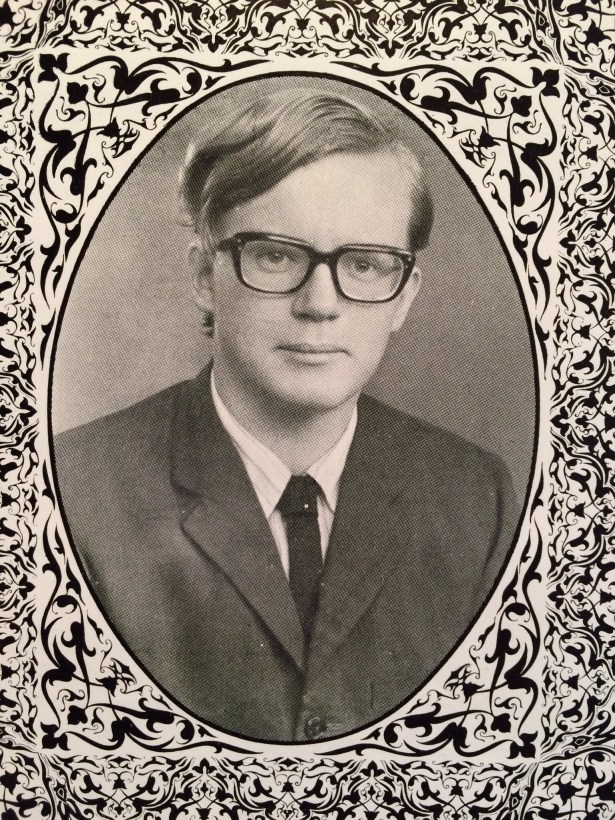

My uniform changed over the years: at twelve, we finally got to wear long trousers; at fourteen, grey suits and shirts gave way to navy suits and white shirts.

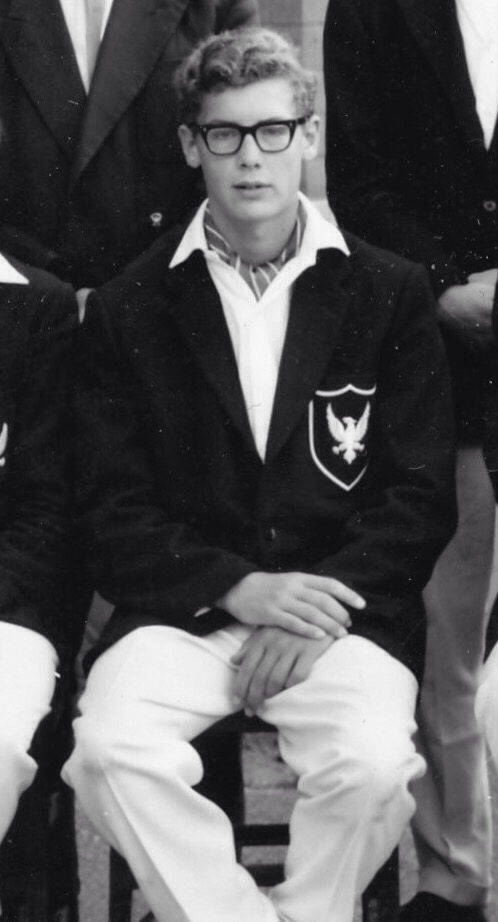

Looking smart in navy and white.

Coincidentally, this became my armour of choice almost thirty years later. I could go on for far longer about clothing and conformity (this applied equally outside school, as we vied to outdo each other to fit in as punks, mods, greasers, indie kids or potheads) but I have to buy Christmas cake ingredients.

Performance

Dress is performative; much of my life at that time was a performance. My first play was aged six, in Pakistan; at Bedford I clocked up fifteen plays. One performance sticks in my mind: I played the Headmaster in Unman, Wittering and Zigo, the stage version of a very unnerving film starring David Hemmings. I was first on. The stage in the Great Hall, a vast space on which Malcolm McDowell appears as Flashman at the opening of Royal Flash, was empty except for the two of us: the Head and the new teacher. In front of us was a scary sea of parents, pupils, relatives and teachers. Hundreds of eyes. In that moment I was equally terrified and exhilarated. I get scared before I perform, but I was prepared: I had learnt my lines, we had rehearsed and, above all, I was dressed for the part. I swept to the front as the lights went up, looked out into the darkness, arranged my gown as I had seen our Head do so many times and began to speak. And as I spoke, I thought, this is my stage, this is my audience, this is brilliant.

And I wonder how I came to teach…

This is Adrian Barlow, the young teacher who taught me to act as well as to love English.

Difference

I will conclude my review of my own school days with three examples of significant difference.

Firstly, the subtle signs of rank: monitors could wear different coloured sweaters. They could even wear coloured waistcoats. And they wore brown shoes, in contrast to our black ones. They could walk across the grass; we had to walk round. And, though they could no longer beat us, they could make our lives miserable. No wonder John Fowles hated it (I think it suited Paddy Ashdown).

From the Head at the bottom to ordinary schoolboys at the top.

Destined never to hold any rank and, in fact, to be expelled, I didn’t get to dress up like this. I now wear brown shoes with my suits, as much in deference to the school dress code of my youth as to thumb my nose at ‘City’ conventions, of which more later.

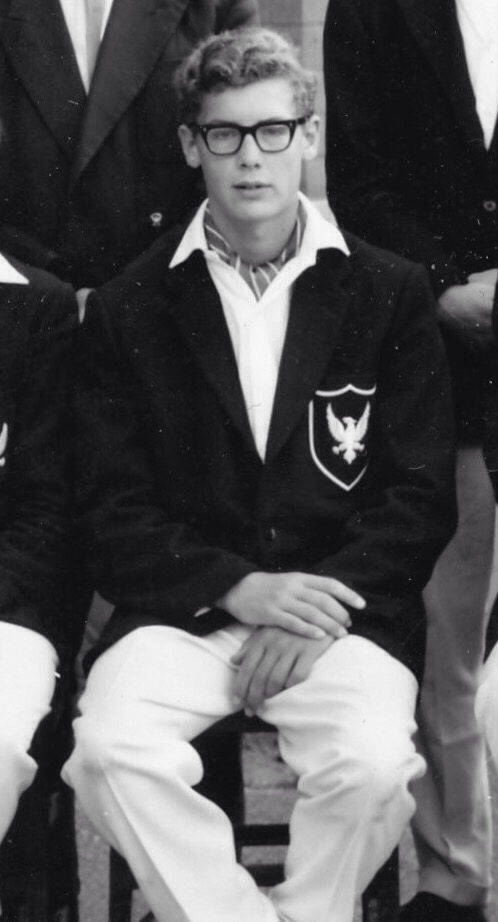

Secondly, the sign of sporting accomplishment. At twelve or thirteen, a little blue or red ribbon on the lapel indicated all-round prowess; unable to catch, kick or throw a ball and possessed of two left feet, I had no such ribbon. Further up the school, there were ties, blazers, scarves, even white trousers if you rowed. Badges, blazer trimmings and tie stripes spelt out our accomplishments. Bedford was, above all, a sporting school: the head of Geography was the England hockey captain for starters.

This picture is from the sixties; it could easily have been twenty years later.

No one wore different clothes for being clever, so I decided to become good at sport. One avenue remained open: there are no balls involved in rowing, and I have very long levers. I am also extremely determined, when I put my mind to it. So I trained and rowed fourteen hours a week, partly because I loved it but partly so that I could earn the tie, the blazer and the scarf. To this day, I treasure my “Trial Eight wrap”, a huge blue woven scarf with three stripes: emotionally, it is more important to me than my degrees. I can do ‘clever’; ‘sporty’ was a true struggle.

The wrap I so coveted.

Finally, for one teacher, clothing showed outright resistance. ‘Bunny’ Warren wore jackets, but sometimes they were motorbike jackets. He wore trousers, but they were jeans, soiled with grease from the motorbike he occasionally rode across the lush playing fields. His hair was over his collar, his face stubbly long before ‘designer stubble’ became a thing. Bunny wasn’t there for long, but he shone, in all his short, greasy, biker chic.

I left school with a strong need to fit in, a powerful desire to compete and excel, and an equally strong and sometimes self-destructive streak of idiosyncrasy. In my next instalment, I will address conformity and transformation at university.